Background

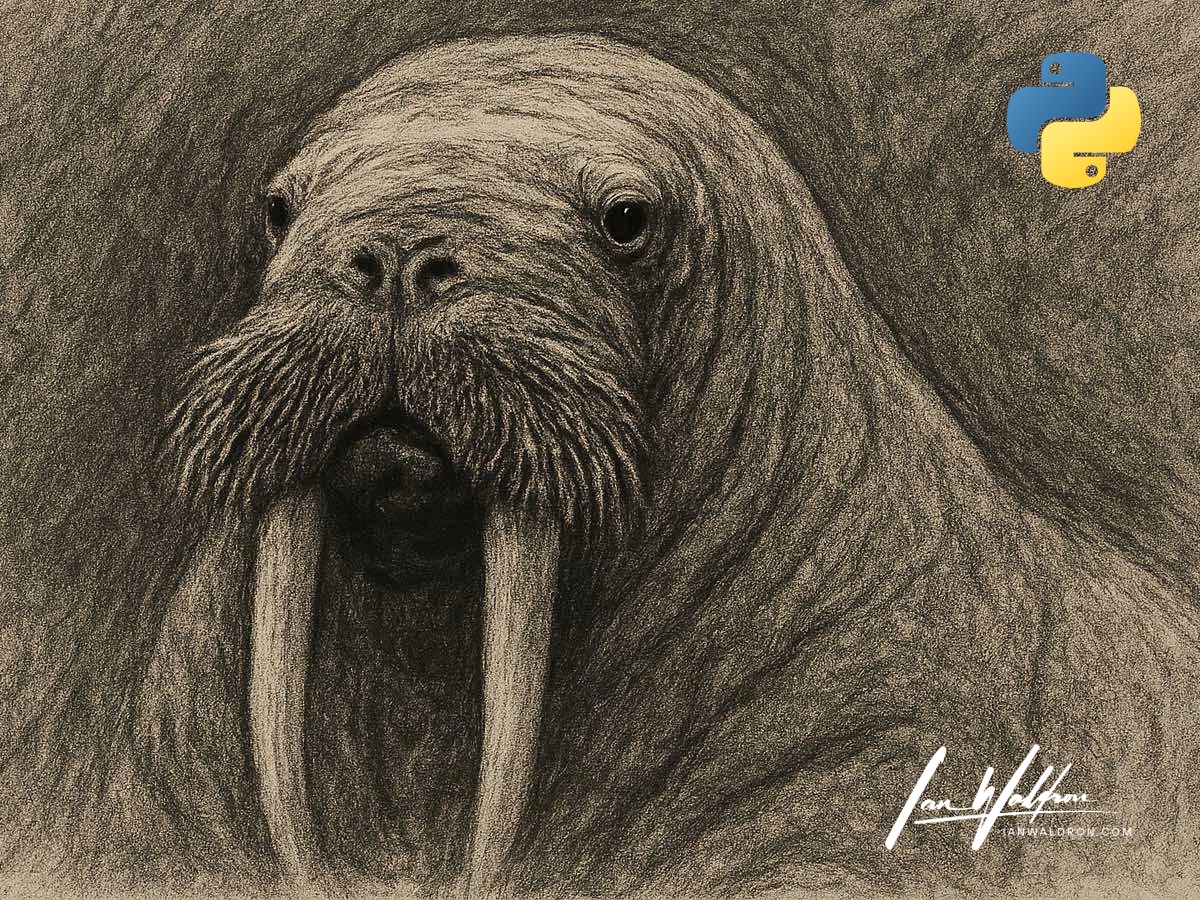

The Python walrus operator (:=), so named because it resembles the eyes and tusks of the mammal with the same name, is one of my favorite additions to Python in recent years. The walrus operator is used to construct assignment expressions, which we'll explore in the next section. It was introduced with PEP 572 in 2018 and made available with the release of Python 3.8 in October of 2019. Let's take a look at how the walrus can add value in your code.

Basic Usage

An assignment expression is simply an expression that contains an assignment. That might sound like a redundant re-wording but it really is that simple. Consider a real-world scenario: you need to perform some transformation on a value but you're unsure if it's present.

name = kwargs.get('name')

if name:

name = name.strip()Before Python 3.8, this pattern was the only option available. This feels redundant and isn't very elegant. The name variable is only being used within the conditional expression block, yet it still requires an assignment statement. With the walrus, we can eliminate a line of code and combine the conditional expression with the variable retrieval and value assignment.

if name := kwargs.get('name'):

name = name.strip()This is more concise and readable.

Furthermore, the variable established is still available outside the expression block, even if the expression evaluates to False.

kwargs = {}

if name := kwargs.get('name'):

pass

print(name)

# output

NoneWe can see this by inspecting the local namespace.

kwargs = {}

if name := kwargs.get('name'):

pass

print(locals())

# output

{'kwargs': {}, 'name': None}Already, you can see the practical value of the walrus operator.

Comparisons

The example in the previous section contained an expression that only evaluated to True or False. We can take this a step further with comparisons.

kwargs = {'guest_count': 5}

if (guest_count := kwargs.get('guest_count', 0)) >= 5:

print("It's a party!")

else:

print("Underattended.")

print(guest_count)

# output

It's a party!

5Note, because the walrus has lower precedence than the comparison (>=), the surrounding parentheses are required. We can see this by dropping the parentheses and inspecting the output.

kwargs = {'guest_count': 5}

if guest_count := kwargs.get('guest_count', 0) >= 5:

print("It's a party!")

else:

print("Underattended.")

print(guest_count)

# output

It's a party!

TrueThis still works in our particular case, but we're probably not expecting guest_count to be assigned a boolean rather than an integer.

Other Useful Patterns

The first two examples lightly introduced the usefulness of the walrus, but this is just the beginning.

While Loops

# before

line = file.readline()

while line:

process(line)

line = file.readline()

# with walrus

while line := file.readline():

process(line)The walrus eliminates the need for the initial assignment.

List Comprehensions

The walrus shines when you need to transform a value and then filter on the transformed result.

results = [squared for x in numbers if (squared := x ** 2) > 100]Regex

# before

match = pattern.search(text)

if match:

print(match.group(1))

# with walrus

if match := pattern.search(text):

print(match.group(1))These patterns eliminate redundancy and make your code more expressive.

Hazards

Assignment expressions and assignment statements differ in key ways that might not always be obvious.

Multi-target assignments function differently with expressions.

a = b = 10

print((a, b))

# invalid syntax

# a := b := 10

# equivalent would be

(a := (b := 10))

print((a, b))

# output

(10, 10)

(10, 10)Commas function differently.

x = 1, 2

print(x)

(x := 1, 2)

print(x)

# output

(1, 2)

1Other potential hazards where support is limited or unavailable include packing, unpacking, and augmented assignment.

Final Thoughts

The walrus operator introduced with Python 3.8 is a powerful tool to make your code more concise and readable. The article introduces a handful of simple patterns but we've just scratched the surface. Give it a try in your next project if you're not using it already. You might just find it becomes an indispensable part of your Python toolkit.